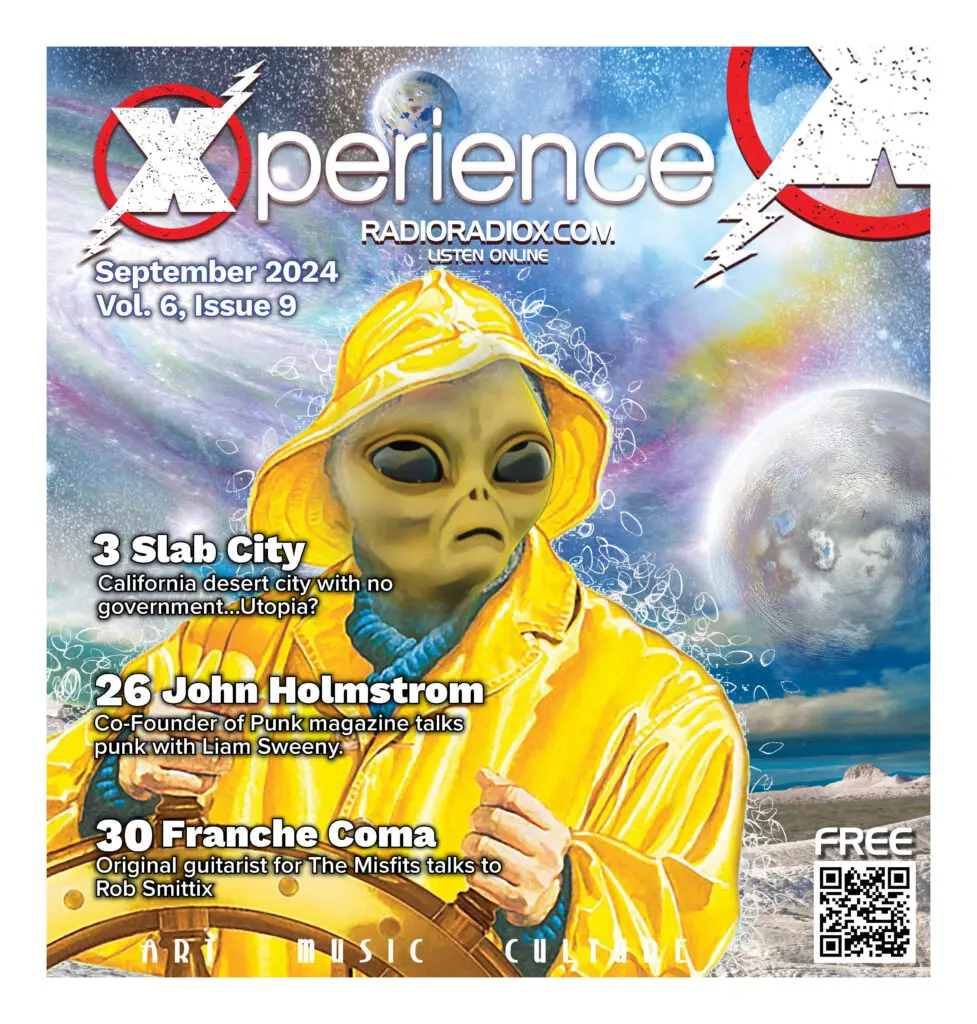

Slab City – An Xperience Article

By Staff on September 1, 2024

Slab City – An Xperience Article – by Liam Sweeny.

The Southern California desert. Sixty miles south of Joshua Tree National Park, there’s a city sandwiched in between a bombing range and the south end of the Salton Sea, a body of water so toxic that if the law meant anything, no one would bask on its beaches or walk through its surf. There’s no zip code, no city council to vote on one and no mayor to give a rousing speech persuading the residents that they need one. And no cops will arrest you for stealing someone’s mail.

Welcome to Slab City, with a population of a couple hundred or a couple thousand, depending upon the season and who you ask. A place where you can be free and so can everyone else, and you realize that freedom is a fire that can warm your heart or it can burn your bones. It’s on Youtube, a Gen Z bucket list, a haunted house challenge, but the truth is very much alive.

Sira is a dancer. She’s self-taught and she moves like no one with a little touch of everyone. She is a docent at Salvation Mountain, a city landmark, a giant labor of God’s love built entirely from the vision of one man, Leonard Knight.

“He came out here and his original intent was to inflate a hot air balloon,” Sira said. “Like a 200-foot-long hot air balloon out here that said ‘God is Love’ on it. And he unfortunately didn’t get to do that because the environment that the hot air balloon was in didn’t really lend itself to that too much. So he made the mountain instead.”

“Everything you see on the mountain he did basically by himself. And he only got really donations for it, but he made that whole mountain basically on his own with his initial intent to show you that he loved God, that was his big thing. He loved God. But as the times rolled by and people evolved, he evolved as well and he started to make the mountain for everybody, long as you have love in your heart, you know, you, nothing can go wrong. Keep that sense.”

Sira is at home in Slab City. It is summer, a time that tests the mettle of slabbers, and some might say signifies the truest of them. It was 124 degrees when we spoke. She understands the true draw of such a fierce place.

“I don’t care how they are in Babylon,” she says. “but when you come out here you have this energy, you know, you feel like you can be yourself and it’s so natural and that creates a lot of uniqueness with the people who come out here. Even big artists when they come out here, you get to see them be themselves instead of following the rules if that makes sense. And it’s really refreshing to see, especially nowadays because people have such a hard time being real. So you don’t have that problem here.”

Her name is Simcha. It means “to find the blessing.” Her search, and the weather, has found her on the holy mountain of Shasta, her van parked near a drum circle that had been going on for hours, drummers hopping in and out, threading the beat. Her dog is treated to scraps of bone and meat by the drummers and fellow nomads. She lives her life riding the waves of providence, and the current had once taken her to Slab City.

It is in Simcha’s nature to help, to serve, and in the slabs she was quick to find like-minded souls.

“And, um, my campmate Chuck and I both kind of fight death for people who would come to us and nearly die, and then we would bring them back to life. Once I did a drum circle for that because my friend had had a heart attack; it happened five or six times with different people and they would come to us and be like ‘I came to the desert thinking I was just gonna come kill myself. And then I found you guys.’ And we called ourselves the Pillow Patch, like a safe place to rest. And then we would just play music. We were a sober camp except we would smoke a lot of pot and I would experiment with my journey. But there was no alcohol and there was no meth, none of that harder stuff.”

A blended truth is that the slabs are dangerous, and they can be. The desert is rough. And some who come there are escaping Babylon, what they call the outside world. And some come to do meth and hide out from Johnny Law. Simcha found out one night that she was “bad for business.”

“They lit my place on fire in the middle of the night, and I heard a voice saying, ‘Get up, you’re in trouble,’ she said. “And I got up when my ceiling was in flames and I grabbed my dog, and I ran out, and I tried running back in there, which I shouldn’t have. Thank God I woke up and like screamed for my campmates.”

He is called Water Boy. It’s a tattoo that spans his back, reining in the darker prison ink that would have him unacceptable in Babylon. He is an outlaw and a vigilante, and a father and the driving force behind Slab City’s soup kitchen. If the slabbers have a sheriff, it’s Water Boy.

Law and justice exist in Slab City, but it’s stripped down. With two girls, Water Boy makes sure that no one on any sex offender registry is welcome. And not being welcome is known to the State of California to cause ill health outcomes.

Water Boy is tough and human, two necessities of living in an inhospitable autonomous zone. But things get to him. When a 67-year-old drunk was burned alive and the murderer came into coffee hour to brag about it, Water Boy rallied the community to encourage the murderer to turn himself in. How that happened was not within the purview of our conversation.

But one of Water Boy’s biggest battles is misconceptions about the city on social media.

He explains. “We have a really bad reputation online and I’ll tell you why. I’ve been here for about 17 years, right? Give or take. I might be a year or two off because time starts to fluctuate out here a little bit, a little different. But so for years and years and years, like when I first came here, it wasn’t on Youtube. Youtube wasn’t even a thing.

“So now Youtube started to blow up, the internet started to blow up in Babylon. We didn’t have reception out here. You guys have cell phones. We did not, we still have shit reception here. So you would come here and be like, ‘Oh, one night in the lawless town of Slab City, come live in the lawless town. Or, you know, I spent a night in a lawless town.’ It’s not lawless dude. We live in California.”

The real story is far more nuanced, and in some ways, Slab City follows more ancient laws that the “civilized” world has tossed by the wayside.

”I guarantee you right now if my car breaks down or my minibike, whatever I’m riding breaks down, and I need a tire, I can go to my neighbor and be like, ‘Hey, we got an extra tire laying around, we’re gonna find a tire inside Slab City,” he said. “Even if you’re not from here. Slap it on your car and get you back on the road because we don’t want you stranded here. You’re gonna die if you’re stranded here. If you come here and you tell me, ‘Hey homie, I’m hungry,’ I’m gonna go. You can’t do that in your neighborhood. Probably very rarely. I can go to my neighbor and be like, ‘Hey, homeboy, I’m hungry as fuck. I don’t have nothing in my house.’ My homie’s gonna give me something to eat and it’s not even my home. I can walk at any random house, but I mean random, any random house and ask for help and then we’re gonna help each other because we’re desert dwellers and we’re a small community and we know we’re the only thing we got.”

Slab City is built on liberty and survival. Doing what you want, being your true self; maybe it can’t truly be done from the cubicles in skyscrapers or the chem-lawns in suburbia. But in Slab City, you only have to survive a desert that wants to desiccate you. And for the 200 to 2,000 residents (Water Boy puts it at about 450 steady) it’s a welcome crucible.

RadioRadioX

RadioRadioX