Ian Macks’ “Identity Crisis”: The Right to Exist in Full Form

Written by BradQuan Copeland on December 29, 2025

Perhaps, I thought, this was the way of the world. It would hunt you and kill you just for being who you are.

– The Creature, Guillermo del Toro’s “Frankenstein”

There’s a rather uncanny paradox inhabiting the world at a subconscious level. No one asks to be here, yet we’re spat into existence and blanketed with the false notion that we can be whomever we want, only to be sh** on for embodying the very essence of who we are.

Glares spiked with judgment, paired with abrasive whispers, intoxicate the once-innocent palate of the neurodivergent being, forming a lens through which reality is perceived in a state of perpetual skew.

When nature fails to nurture, it gives way to the colossal invasiveness of rejection, misrecognition, and abandonment. These forces swarm the sky in an incessant, low, rasping roar, eclipsing all light as they dismantle fields, trees, and strip vegetation bare. Where famine reigns, love dies. Only rage remains, fueled by a gnawing gut that longs to cut through nerves, tendons, and vessels, desperate to finally reach the light promised by the pursuit of happiness.

Such cataclysm defies the very notion of meaning. Yet this remains a lived reality for many who possess the capacity for greatness but cannot see past the hovering clouds of their own interior forecast, a monsoon of acid rain seeping into wounds left raw, unhealed, and unwilling to seal.

This is the risk of wearing one’s heart on their sleeve without the means to shield it from the ruin of a ruminating past or the uncertainty of an ominous future. Pain is only beautiful when it can be tamed, honed, and channeled into something universally felt. There is no singular pathway to that transformation, but for local artist Ian Macks, it exists through the brilliance of his raw literature, most notably his poetry collection, “Identity Crisis.”

I was honored when he reached out to me via Facebook, asking if I’d be willing to write a piece on his work. While I was genuinely interested, my plate was loaded with other projects at the time, and the publication I frequently contribute to doesn’t delve much into poetry. So, after a few weeks, once my creative space had cleared, I made sure to circle back. Where it ultimately landed was of no consequence to me. The only thing that mattered was getting it done.

He was kind enough to supply me with the manuscript via email. It was a quarter to eight on a Tuesday evening, and my mind was profoundly suspended in verdant vapor. I got no further than the preface before I was cornered by the heaving presence of his unapologetic truth. The warm, gamey, iron-rich metallic musk on its breath reeked of a tortured life fed up with self-cannibalizing. It unleashed a bestial bellow that demanded to be heard by any means necessary. The sheer density of its force bristled the hairs on the back of my neck, my heart swinging wildly, a pendulum battering the brass of my chest.

This was a mirror pressed against me, stirring my anxiety into a buzzing violence that only my final dose of Buspar could settle. “What the f***?” I asked myself in disbelief as long-buried demons were resurrected and marched thunderously to the forefront of my mind. The effect was almost cacophonous, a ruckus of voices shouting over one another, rattling my brain until it forced me into retreat and made it obvious that this was something I needed to return to with a clearer head.

Two days later, I returned unsullied, fully immersing myself in the literary turbulence of what it means to be Black, autistic, and hypersensitive in a society that demands silence, compliance, and gratitude, especially of a man.

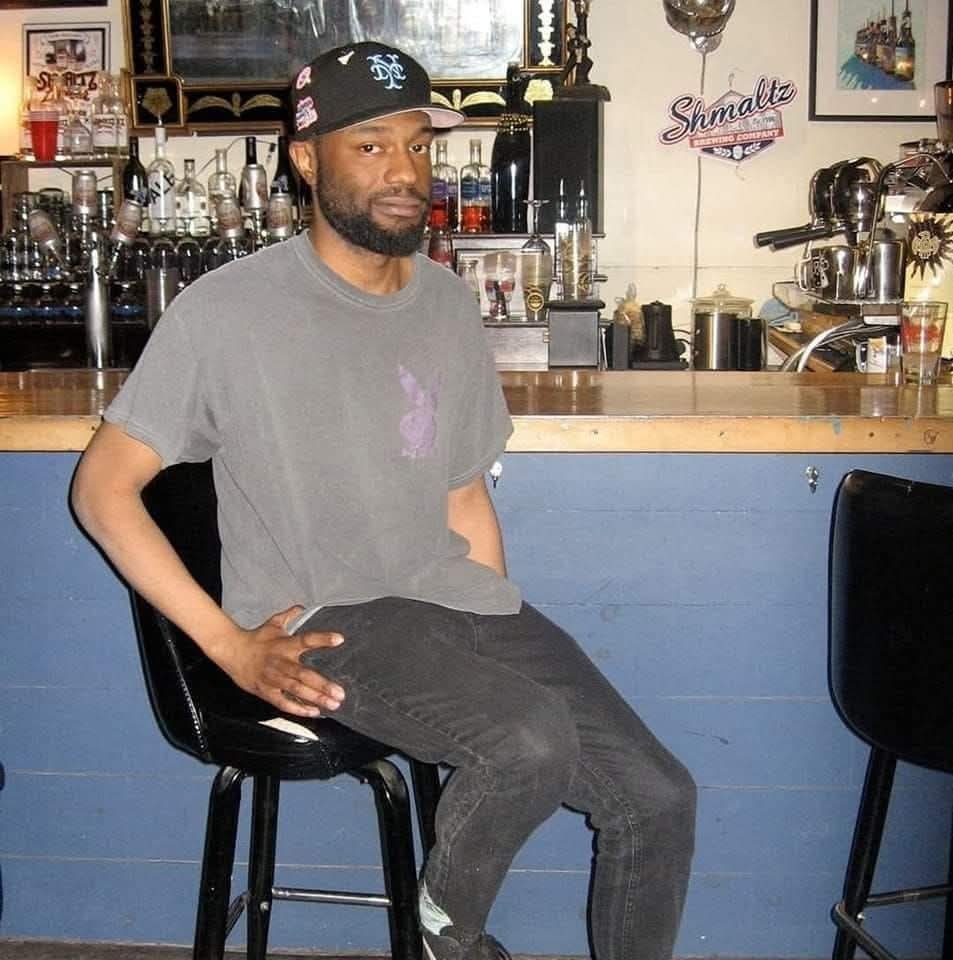

Decked in a pilled Philadelphia Eagles beanie, a lived-in black Columbia Pictures hoodie, sweats, and gray Yeezys weathered through atonement, I was granted the opportunity to sit across from Ian in the tranquil setting of Stacks Espresso Bar on Lark Street. There, we dove into a deep dialogue, and one of the first things I asked was when emotional awareness stopped feeling protective and began to suffocate. His answer was immediate and candid.

“Probably when I got addicted to coke,” Ian said, describing the precise moment when tenderness transitioned from survival response to hindrance.

Raised by a dual-employed single mother in the Bronx until the age of ten, he moved through the unease of adolescence before the belated presence of an emotionally absent father entered his life. He described ancestral emotional inheritance as something he internalized long before he could verbalize it. “The emotional burdens my parents went through are part of the story,” he said, “but they’re not what defines you.” This is a reality many of us learn later in life, as the hurt inner child grows alongside our imperfect selves, craving more attention and crying louder until unmet needs are satisfied, often through self-destruction.

What I admire most about this project is that it paints a muddied picture of a man carrying humble defiance. At its heart is the right to exist fully without surrendering to hollow boundaries that dampen the will to oppose injustice and resist tyranny. “You become numb to what makes you you,” Ian said of seeing himself through others’ expectations. “It takes away your fire.”

Drifting carefully from outrage and depersonalization toward accountability and self-authorship, this book serves as a forensic self-analysis of a fractured core. It excavates the frustrations of a socially conscious being worn down by liberal hypocrisy, racism, and the weight of societal expectations imposed by a supposed home he can scarcely call his own. A great deal of that fracture, he explained, wasn’t mindfully chosen.

“Identity Crisis” showcases not only Ian’s natural disdain for disparity, but also a well-mannered humanity that moves with respect for others despite it. That level of emotional maturity has been earned through inherited trauma and battles with drug and alcohol addiction, hardships that have kept his head intact while sharpening an intellectual fervor refined through adversity.

“Only the strong go crazy; the weak just go along,” is one of my favorite quotes from Assata Shakur’s 1987 autobiography, and one that Ian embodies fully. The vigor of his literature merely sets the stage for an individual who, even if he himself doesn’t change the world, may provide the spark for someone who can. That sentiment echoes the words of yet another Shakur, who once carried the weight of the world’s gaze before his untimely demise.

Written in a journal-esque poetry–prose hybrid, dense with energy yet accessible in presentation, Ian’s artistic cocktail ignites the chest. It blends traces of James Baldwin, Charles Bukowski, and Langston Hughes into a contemporary setting that trudges through the inefficacies of the Capital Region. His voice took shape first within the working-class grit of Troy, then later in Albany, where, in adulthood, he worked steadily to shed the congested shell of only-child syndrome and step into the relative comfort of the art scene, networking with like-minded creatives.

That same sincerity and guileless relationship to the arts extends into the book’s treatment of sobriety. In “Identity Crisis,” sobriety isn’t framed as clarity so much as confrontation. Ian described it to me as “a pain in the ass,” a stripping away of crutches that forced him to sit with consequence rather than outrun it. Responsibility, he said, offered something rage never could: the ability to look at himself without flinching. “One of my biggest strengths as a writer is putting myself in the moment,” Macks told me. “Being there to witness and feel in order to get a full objective view.” It’s that sustained presence, I believe, that keeps him grounded in a hard-fought sense of peace, shaping an ever-shifting pilgrimage toward sobriety.

In that sense, “Identity Crisis” becomes a silent contradiction to the Creature’s conclusion, not a deflection of the hunt, but a refusal to conform to it. Ian doesn’t ask society for permission to exist, nor does he contort himself to fit within the rigid constraints of approval. Instead, he documents the cost of being seen as monstrous for simply existing as a neurodivergent Black man in America, yet chooses to live in full form despite it: scarred but unbroken, fiercely accountable, and unwilling to relinquish his humanity for comfort. Where the world coerces the marginalized to vanish or assimilate, this book insists on something far more vital: owning one’s truth in its entirety, no matter how unsightly, so the sting of judgment loses its potency, and the wounded are spared from becoming the very hate that hunts what is.

RadioRadioX

RadioRadioX