Beach Interviews Dweezil Zappa

Written by Richard Beach on March 5, 2020

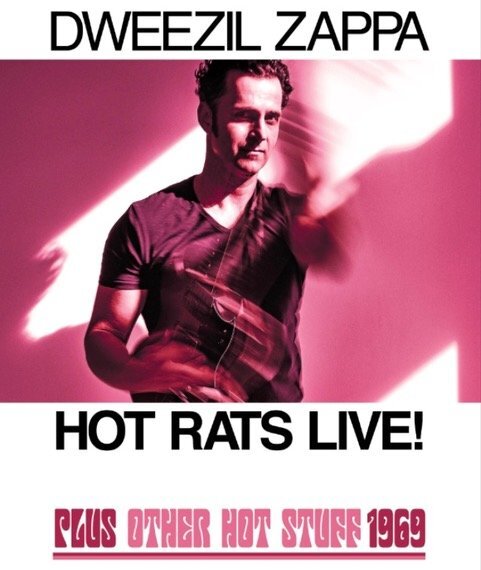

Having taken up the mantel of honoring and presenting his father Frank’s music, Dweezil Zappa has turned a legacy into a quest. This year, he is doing Hot Rats Live and more from 1969, the year he was born. Honest, gracious and more hard working than working than we can imagine, he took time out on tour to speak with Radioradiox about growing up, music, performing and the PMRC. Enjoy.

RRX: Thanks for joining us. I want to start at the very beginning. Having done some research, it was fascinating that when you were born, the hospital would not let you have your name, which I thought pretty interesting. But then, when I found that on the birth certificate, you were registered as Ian Donald Calvin Euclid Zappa. Those were some of the guys in Frank’s band at the time. What do you think about how he came up with that, and what it meant to you over the years?

DZ: Well, first, my first name was always Dweezil, and it was on my birth certificate. Those were my middle names, Ian Donald Calvin Euclid. But those were removed when I found out that those were my middle names when I was about five. I didn’t like any of them, so I said I don’t want any of those. They were actually taken off of my birth certificate.

RRX: I found it interesting that, given who they are, that those were the names that popped into your dad’s head. I don’t know whether you did.

DZ: Well, yeah. It didn’t have any meaning to me at the age, other than I didn’t like the sound of any of those names. Dweezil sounded better to me at that time. But ultimately, it’s one of those weird things where somebody decided yeah, you can’t name a child this. You’re gonna have to have a regular name or we’re not gonna let you have access to your child. So, my dad just gave a host of names. Those were something they couldn’t complain about. Then, that was the solution to that thing. But the other thing that was on my birth certificate was under religion, it said musician.

RRX: Before we move on to your first recording, those of us of am age were watching the PMRC and congressional hearings. Your dad came up and Tipper Gore she thought it’d be fascinating to see the toys that you guys played with as children. Of course, Frank’s answer was hey, come on over, see them. They’re in the closet.

DZ: That was Senator Hawkins who –

RRX: Was it Hawkins?

DZ: Yeah. But yes, she was a wretched lady.

RRX: Yeah. I would imagine that by and large, for you it was a normal childhood. It was who you were. It’s what you did. You went out and played with the kids in the neighborhood. You played music Would that be how you would categorize how your childhood was?

DZ: I think everybody would view whatever their situation is growing up as normal ’cause that’s all they know. But we certainly didn’t do anything that was abnormal for traditional standards of what children do when they’re growing up, playing with toys or stuff like that. We didn’t have weird toys, we didn’t do strange things. So yeah, it was nothing of anything to speak of.

RRX: I want to get to the first recording you made, back in ’82. You were 12, 13, and you did “My Mother Was a Space Cadet.”

DZ: Yeah.

RRX: You wrote it with your sister and Steve Vai. That had to be really interesting. Is there anything in particular about that you recall, whether it was about process, about the writing experience and things of that nature that really stood out for you?

DZ: Well, I had a riff that I had composed that was a pretty heavy duty guitar riff. I had only been playing guitar for a couple of months. I was learning how to play by listening to records and picking out things that I could from just listening. But my dad had Steve Vai in his band at the time, so he showed me a couple of chords and some ways to relate chords to scales. So, I had a little notebook of lessons that he gave me. It was five or six lessons in a little notebook.

During that period of time, I had showed Steve this riff that I wrote and he showed me a Lydian chord because we were talking about different scales and modes and things, so he showed me this thing. It ended up being something that got attached to the first riff that I wrote. That is how his part of the songwriting thing came together ’cause the chorus part became this Lydian chord thing.

The song has really got only three little sections in it. The lyrics were stuff that were all about my mom because she used to basically tune out and you couldn’t get her attention, as a kid. You were like, “Uh, we have to go to school now,” and she’d be sitting there reading the newspaper. Like, “Yeah, we’re late for school. We have to go.” She just wouldn’t even take her eyes off the newspaper or whatever magazine.

The point is, the song itself is a bit of a sense of humor song. It’s the first song that I remember really writing, and my sister added a couple lyrics into it. But the rest of the story that’s interesting is that it was actually produced by Edward Van Halen, and Edward Van Halen played a little bit of guitar on the intro to the song. There’s a slide guitar part that he plays the intro on.

So, there’s a lot of history to that experience. And being the very first thing that I ever recorded, working in the studio with Edward Van Halen and all this stuff. He was joking around with us, saying, “I don’t know what to do with you guys. Do we have to take a milk and cookie break?” We’re all like 12 years old.

RRX: Did you keep the notebook?

DZ: Oh yeah.

RRX: Oh. I will make an extrapolation ’cause we all know that your dad kept pretty much everything. Do you document, record and keep your own set of archives? Is that a part of the pattern of what you do on a regular basis?

DZ: No, I don’t really care about that stuff for my own purposes, really. I have that notebook, but generally speaking, I’m not a collector of things. I don’t keep scrapbooks of things. I know some people are interested in having some kind of an archive of all that stuff, but I’ve already experienced it by living it. I don’t need to go back and check it out again.

RRX: I’m gonna fast forward a little bit. Later in the ’80s, into the ’90s, you had an interesting acting career. You were an MTV VJ for a short time. You were in Pretty in Pink, Running Man, and the TV show Normal Life. But the best of them, in my estimation I think probably interesting to our readers, is the fact that you indeed were Ajax Duckman, which was, I think, one of the great cult cartoons ever. How was that process for you? Was that an interesting project? You did it for about three years. What are your memories of it, and then secondarily, were there any takeaways from working on that?

DZ: It was a fun show. It was quirky animation. The company, Klasky Csupo, they were pretty popular at the time, during Rugrats and a few other shows. They had a style of animation that was popular at the time. Duckman was all angular and weird, and they got to go pretty twisted with a lot of the stuff in there. It operated on a few levels. It wasn’t necessarily just a kids’ show kind of thing, you know? But it was –

RRX: Well, neither were the Warner Brothers cartoons.

DZ: Yeah. But the people that were in the cast were interesting and fun. I remember Tim Curry being the guy that made me laugh the most. He gave a master lesson in how to deal with artistic integrity. For example, he wanted to read the material the way he thought it was the funniest. When the producers or director would ask him to change something, he would politely say, “Oh yes, of course.” They would say, “Here’s how we’d like to do it,” and they’d give him a line reading. He’d say, “Oh, sure. Sure.”

He would listen to them, and then he would do it only the way that he wanted to do it. Each time, they would say, “Okay, that was great. But now, can you try it like this?” and he’d say, “Absolutely.” And he would do it only his way. He has a British accent, but when he does an American accent, he does a really obnoxious version of an American, and he would over-enunciate certain things.

In one case, he was mispronouncing the word NASA as NAWSA. So, they kept saying, “Okay, that’s great. But can you say NASA instead of NAWSA?” He said, “Absolutely.” So, every time, he said NAWSA. They never got a single take where he said NASA, and that is the art of keeping your artistic integrity. Don’t give them the option because they will use it. He kept going, and it was hilarious to watch because he did it so amazingly well.

RRX: That had to be fantastic. It had to be fantastic to watch, it really did.

DZ: Yep.

RRX: Around ’96, you began a project called “What The Hell Was I Thinking?” The last reference that I can find to it was when you did really a wonderful post when Malcolm Young passed, which would have been 2017. Is that still an ongoing project? Are we going to see the fruits of it? Because I couldn’t find anything that said it’s been released, I am guessing perhaps it’s still in production?

DZ: It is still in production. The thing about it is, it’s always been an idea of mine to make it the equivalent of an audio movie. The whole premise behind this thing is that it’s a piece of music that constantly morphs and changes styles, but it also changes the environment that the music is in. Over the years, it’s been on different formats. It’s been on analog tape, it’s been on various versions of digital tape and now, it’s in computer form.

But there were a couple of technical problems that came up during the process of recording that at one point halted things. But really, the delay has been that I’ve been touring the last 15 years, and I haven’t had any time to finish it. One of the things that has renewed my interest in working on it again is that with the proliferation of the Atmos. There are great opportunities for mixing and delivering music in this format., This particular project will be cool to hear in surround sound, and have things moving around your head, and all that kind of stuff.

My goal is to finish it in the next year or two, but as an Atmos project. It’s really an audio movie type of presentation. It’ll be a multi-channel experience, a binaural audio movie.

RRX: I find intriguing that you mention binaural sound. Locally, a guy by the name of Todd Lopez, his firm is called ZBS Media, really interesting audio projects for radio. One of the things he has is one of the very few kunstkopf recording heads. A head that was built with auditory input to the two ears, and literally you record in 3D around a mimicked head. I don’t know if you’ve ever seen it, but it really is a fantastic thing.

DZ: Yeah, there’s a few companies that have made those kinds of things that mimic the human hearing system. But now with Atmos, there’s a way to deliver an experience like that in regular headphones. That’s the thing that’s going to be very interesting for the future is that in the very near future, you’ll be able to be sitting on an airplane or sitting on the subject, listening with earbuds and hear full binaural 3D surround sound.

It will alter how people experience music because music has been so devalued, but this is one of the ways that music can have a resurgence and be revalued because any song from any era can be presented in this format, and it will heighten the experience of the music. Old records, new records, creating new recordings in that way. It’s exciting and something that I look forward to. But yes, “What The Hell Was I Thinking” will eventually get finished, but I plan for it to be in that kind of format.

RRX: I can’t wait for it to come out. I’d like to talk gear. I’ve got a bunch of guitars that I can’t play worth a tinker’s damn. My favorite is a Gibson 1980s reproduction of the 1960s Les Paul Junior Double Cut dual Humbuckers in TV yellow. You have a lot of guitars from which to choose. I know you play an SG, you’ve got a Roxy SG, you’ve got a Stratocaster. What’s your favorite rig to play? What’s the one when, whether you’re on stage or whether you are rehearsing, that just makes you happy?

DZ: It all depends because I’ve always been the kind of player that whichever guitar I pick up I’m gonna play a different way because the guitar just feels different. Sometimes you hit on certain combinations with amps or effects that work best with that particular guitar, and things get inspirational. But the biggest challenge for me is that we cover so much ground in recreating the music that my dad made that I have to be cataloging all of these sounds that I’ve recreated as presets in my guitar rig. So, there’s a few that become standard that I can use with any guitar.

But I’m always tinkering with stuff, so each guitar… I might play a few different ones on each tour. Sometimes I’ve done tours where I only play one guitar all night, sometimes I play three or four different guitars in a show. But it just depends on the material. I think I’ve kind of grown accustomed to playing an SG mostly just for comfort. It’s the easiest guitar to play. But sometimes a Stratocaster will make a sound that you just can’t get from anything else, and that’s just what’s needed. My dad would do that for…he would choose that for certain songs.

So, like I said, depending on material, I’ll have to have a Stratocaster for certain things. But mostly, I get away with playing an SG most of the time. Except on this tour, the Hot Rats tour, I’ve been playing a Les Paul Gold Top that has p90 pickups in it, so it’s a combination of stuff. But generally speaking, I don’t get really too attached to anything ’cause I know that you could be out on tour and something can break or whatever, and you just got to find a way to keep going anyway.

RRX: Speaking of the current tour, Zappa Plays Zappa started, I guess, in 2006. My wife and I, we saw you on that first tour and we’ve seen a number of them since. There was something that struck us on that first tour: you were very quiet. You almost seemed reticent to say an awful lot. In the years that have passed, you’ve opened up quite a bit. Can you provide us with an little insight into how that has progressed as you’ve gone from doing this when you were 36 to now at, dare I say, 50?

DZ: The whole point in the beginning was that I shouldn’t have to say anything; the music should speak for itself. I presented the show in the way that my dad does, where everything segues. He didn’t have much onstage banter that was what you would call typical, where it’s like hey, how’s everybody doing kind of thing. There wasn’t really any of that. There was maybe some interaction that was created for band interjection type of things. Or sometimes my dad would have a particular story that he would share. But it was all part of the musical arrangement and everything.

He wasn’t really ever presenting a show that was a standard kind of thing that relied on the hey, thank you so much for being here. He would say, “Thanks. Hope you enjoyed the concert,” and that’s about all you’d get. So, in the early days, I really wasn’t saying anything because, like I said, I wanted the music to just speak for itself.

RRX: There is a project from Alex Winter called Who the F*@% is Frank Zappa? It’s a documentary that is restoring much of Frank’s vault. Is that anything that you have had any contact with? Is it anything you’re interested in? Or is that part of the legacy that you’re just leaving to itself?

DZ: I’m not involved in that project in any way.

RRX: You’re here in Albany March 11th and you’re doing Hot Rats Live plus more from ’69. That album was dedicated to you back in 1969. First, is this a little more special perhaps than some of the other 50th anniversaries, like the Apostrophe tour, et cetera? Secondarily, you have I guess what I would call a band of young Turks that are with you, some amazing players. Can you speak a little bit to the Hot Rats piece itself, and then about the band that you’re touring with?

DZ: The point is that you need excellent musicians, and that was proven in my dad’s bands over the years. It’s rare that my dad would be able to keep a band together, a consistent line-up, for more than three or four years. At times, I’ve had versions of my band together for more than four or five years. But I’ve mixed it up over the years.

It was hard to keep a band together for longer than three years for my dad because often, people would try to use his band as a stepping stone. They thought, if I can be in this for a little while, then I can move on to my bigger career. It didn’t always work out that way for people. Most of the time, in fact, it didn’t.

RRX: There are a few notable exceptions.

DZ: Yeah, you have George Duke, Vinnie Colaiuta, Terry Bozzio, and Steve Vai and Adrian Belew as examples. There were at least 70 or 80 other musicians or more throughout the years in versions of my dad’s bands.

In any case, the point is that the music is challenging and you need people that can play it. But it’s tough to find the people that have the right professional attitude and are easy to work with. At the moment, the version of the band that I have is the one I enjoy working with the most and we can cover the most ground. The material on Hot Rats, is largely instrumental, which makes it an oddball choice for it being a superfan favorite ’cause typically, people like songs that have lyrics more.

But, this one just has always stood out to people. We do our best to recreate every element of the record, from the production to obviously the notes and rhythms and stuff. But it’s a challenge to recreate the landscape of it with the instrumentation that we have, so. I’m using my guitar to make sounds that are from other instruments, like sometimes I’ll have kind of a woodwind sound or a violin sound, or something like that I will be incorporating into my guitar sound. That’s just part of the process that we go through. We figure out who’s gonna play what and how we are going to make the sounds work.

At the end of the day, it comes together, but it’s a lot of work. But we enjoy it. The fans seem to really get into this Hot Rats full album presentation. Perhaps a bit more than other live albums. We’ve done Apostrophe, we’ve done Roxy & Elsewhere, we’ve done One Size Fits All. But I think there’s just something about the Hot Rats album that gives a feeling, maybe more so than some of the other records. I’m not sure what it is, but there’s definitely something that’s so evocative of that particular era and for a lot of people, this is the first record they ever heard, sometimes the first record they ever bought in their whole life. So, this one just seems to mean a little bit more than some of the other records.

RRX: Finally, as is my habit, I leave my last question as a bit of a free-for-all. I always ask this, so don’t let your head explode too much. What is it you’d like to say to the world? When I say that, it could be about music, it could be about life, it could be about philosophy. It could be pretty much anything that you would like to tell the world that you hope they will think about.

DZ: I’m not much of a philosopher. I spend most of my time living in the moment. I’m not a legacy type of person. But as far as I can see, it’s tough out there in the world. There’s a lot of stuff going on. But I feel like it’s harder and harder to see the good in people when so many bad things are happening. Everybody’s got to hang in there and be nicer to each other.

RRX: Thank you very much for taking time out. We’re looking very much forward to seeing you on the 11th out here.

DZ: Sounds good. Appreciate it. Thanks.

This interview was facilitated by Ingrid Stinebrickner-Capron of Saratoga Springs Digital.

RadioRadioX

RadioRadioX