Lithium, Chptr. 25 – Xperience Fiction

By Staff on February 3, 2026

Lithium, Chptr. 25 – Xperience Fiction – by Liam Sweeny.

Mel watched the sunrise through the windows of the day room as the nurses wound down from the third shift, hanging off the nurse’s station counter that was holding them up. They took in three new people the night before, and they weren’t well off. Mel wished he could say they were worse off than he was, babbling incoherently, restless to the point of needing shot of sedatives; at least one of them did. But Amanda told him that’s what he looked like. He barely remembered coming in.

He wanted to run. He didn’t want to leave the ward; he just wanted to take a foot cruise around the hospital grounds. Maybe he would when they discharged him. Assuming he had anywhere to go. His social worker had told him she could probably get him help, but if that help was a shelter, he’d never go. And he would never go back to Skid Row, even if that meant hitchhiking back to Albany. Since Debra probably had Andy, he had no reason not to go back, except for heartache.

He dreamt of Hope the night before. It wasn’t wild or symbolic; just a walk down the path of the camp, talking, though he couldn’t remember a word of it. She’d probably never forgive him for the way he’d acted. He missed her, but apparently, she was temporary, like Max. There for a time, and he should get used to that if he was homeless.

He had breakfast with Critter and Ramon. Pancakes times two, because why mess with a good thing?

“So when are you getting out?” Critter said.

“I don’t know yet. They were telling me three days, but that was… three days ago.”

“You know, in jail, you mind your business, and you get out when your sentence is up. They can’t just keep you like they can here.”

“Well, it’s not like I got something to go home to,” Mel said. “Shit, I’ll probably be back when I run out of meds.”

“Whatever you do, get here. Don’t let them take you to the state joint. As crazy as it is here, it’s like jail there. Violent people get warehoused there.”

“I was violent here.”

“Nah, not like that,” Critter side. “Chew on your face violent.”

Mel cut eyeholes and a smile into one of his pancakes and held it up to Critter with a fork. Then he ate it.

“Gross,” Magda said.

Critter chuckled. “Nice.”

They went to the first group in the morning. Dealing with Grief was scrawled in black, erasable marker on the small whiteboard eye-level on the wall. It was sparsely attended. Then again, so was breakfast. The new arrivals made for a hard night’s sleep.

Tom was leading the group. Mel had to admit he was trying desperately to stay awake for the preamble. Somewhere in the meat of the meeting, the pancakes and syrup kicked in.

“Can you grieve for someone you didn’t like?” Tom said. “Maybe even someone you hated? Has anybody ever done that?”

Mel couldn’t say he had. He went out for drinks when he found out his father died.

“Was anybody relieved when someone in your lives died?”

Mel raised his hand. Ted pointed at him.

“Mel, would you mind telling us about who died that you were relieved about, and why that was?”

It was personal, and the Mel of even a few days ago wouldn’t have thought it was anyone’s business, but he was getting something out of the groups. Time to give something back. He spoke up.

“My dad. He was… wasn’t a great guy. And when he died, I felt relieved. I guess I was relieved; really I just celebrated, because I hadn’t talked to him in decades.”

“Okay,” Tom said. “And after that, no changes in your life? No depressions, downturns, anything?”

“I went into a really bad depression, quit work… ended up getting evicted. But that was from my ex-wife. I don’t think that was my dad.”

“It could’ve been your ex-wife, and it could’ve been your dad. Do you think it’s possible that you did feel grief over your dad, and it wore you down so that, by the time you were having problems with your ex-wife, your resistance was down?”

Mel ran it through his head until it banged against a box of memories he didn’t have the key for.

“Let’s get off me for now,” Mel said. He’d given enough.

Laura called him to the nurse’s station just before lunch, after the group Understanding Limitations. He walked over, but before he could say a word to Linda, he could see why she’d called him. On the floor, set against a shelf was a large bag. Sticking out of the bag was a canvas.

“I was able to find some stuff lying around,” she said. “I hope they work for you, and you have to do your work in the day room. And you have to avoid the cloth-covered seats. And clean up your own mess.”

“I will,” Mel said. “I know you bought that stuff. Thank you.”

“You owe us that painting for the ones you ripped up. And you’ll probably be discharged in a few days, so you best hurry up.”

Mel set up a makeshift easel out of a highbacked chair covered in a newspaper from the day before. The acrylics weren’t the ones he used at home, but they were the same brand as the ones he got at the camp. She could have cheaped out, and if he was an overworked nurse, he likely would have. He sat there for five minutes and conjured up a visual of nurses, a historical montage in paint of nurses past and present.

As he started painting, he thought of the burnt-out garage and his attempt to repaint “The Son.” It seemed so foggy except that anxiety creeped up in his gut at the attempt to bring it up. His painting technique right then was smooth, even, and it followed the flow of his brushstrokes and the passion of creating colors and tints.

He needed a red for the cross, but he wanted a darker, deeper red. Something more like the blood they’d been surrounded by in the world wars. He looked up to hopefully find the color in the room. And he did, in the woman standing in front of him.

It was Hope.

***

Hope sat across from him, at an angle between Mel and the painting, as if she were the subject. Mel thought of the painting he did of her at the camp. Did she ever even see it? Or did it get buried in a scrap pile when he had his withdrawals? The camp seemed a lifetime ago.

Hope shifted in her seat. Mel couldn’t stop looking her in the eyes.

“I didn’t want to come today,” she said.

“I don’t know how to feel about that,” Mel said. “I’m not saying that in a bad way; I’m just at a loss for words.”

“That’s a lot of words to say that.”

Mel chuckled. “Yeah, it is.” He set down his brush. “So how have you been holding up?”

“I’m a little bit better,” Hope said. “I have a place, sort of. It’s an SRO. That’s like a room, just a room, and I share kitchens and bathrooms.”

“Oh wow, that actually sounds good. How is it living there?”

“It’s loud; I mean, it’s not a four-star hotel but the locks work. I don’t have anything, but when you’re a woman, you need a lock that works.”

“I get that.” Mel fidgeted. He had so much to say to Hope, and he was nearing his meeting with the social worker.

“Look, Hope, I was a huge ass-,”

“You were manic,” she said. “I know what it’s all about. You were not the worst manic episode I ever saw.”

Mel could feel the chill melting in his heart. He saw Hope as responsible for getting them to L.A., despite the fact that he made the decision to go. He blamed her for his mistakes, and he thought about what Tom said in the group about grieving someone you hated. Mel’s dad used to blame Mel for his own mistakes. And Mel was following suit. Maybe he had a streak of his dad in him. Or maybe he was just a human who acted on an irrational impulse. All he knew is that he hurt Hope and he loved her, and those two things couldn’t reconcile.

“I should’ve never blamed you for Andy. That was all me, and I couldn’t accept it.”

“I do understand,” Hope said. “But what you said really hurt me. And I would hate you right now, except that I used it to get myself off the street. So maybe I should thank you.”

“I love you, Hope, I still do. After this is over-,”

“You need to take care of yourself before we’ll ever have a shot at anything,” Hope said. “I came to give you my new address, and to tell you that. When, or if, you have a place, and you can get on your meds, I want you to come by.”

She slid a slip of paper on the chair that was his acting easel, and she got up. She leaned over him and kissed his cheek.

“Bye Mel,” she said. She pointed at the painting. “I like this,” she said. “So far.”

Mel paced the corridors, east then north, his thoughts consumed with Hope. She was okay. She had a place, even an SRO. And she didn’t hate him. Mel thought about the fact that she was the one that brought him to the hospital, and it sure as shit wasn’t Andy that found him in a burned-out garage. Hope did everything and more for him, and she wouldn’t let him, in madness, throw her away.

Andy was still in danger. Mel needed something to grab onto there. He had to get him back from Debra. Which meant he had to get back on his feet. A single room situation wouldn’t do because they’d never let Andy live there. He needed at least a two-bedroom apartment, or even a one-bedroom studio if it was big enough, because he could always give Andy the bedroom and sleep on the couch. Andy would have his own room. But a two bedroom could also get Hope in there.

Mel was in the day room with time to spare when Maggie came to get him. She was joyous, which seemed odd for her. Mel asked her what happened, and she just said, “You’ll see.”

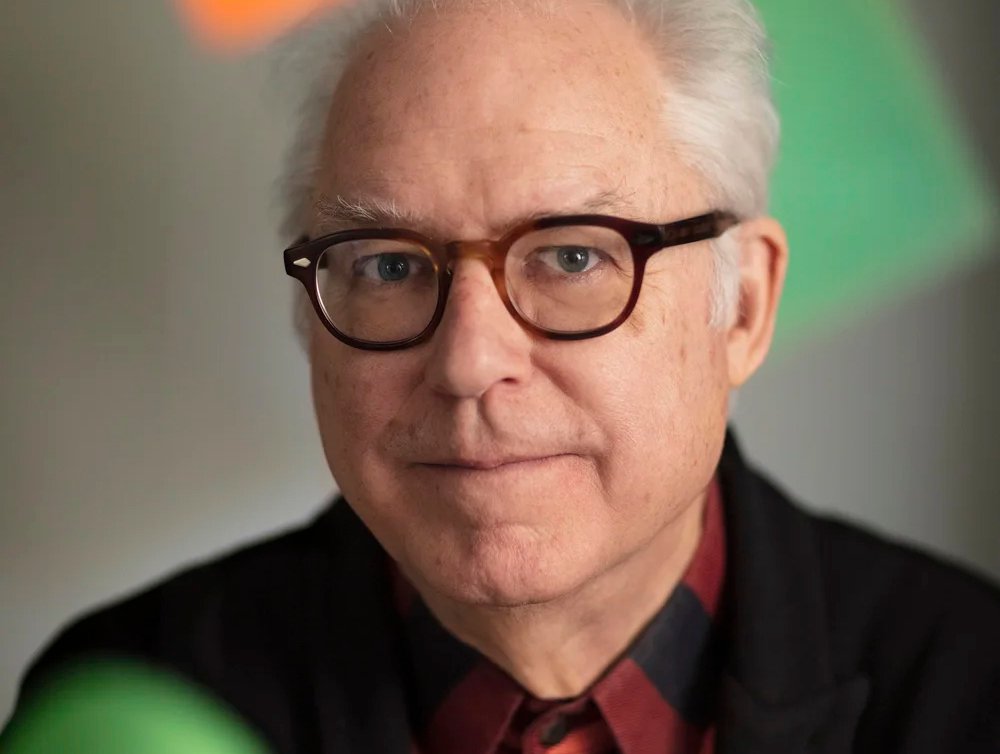

They walked into the second group room, and Mel saw a woman, with shoulder-length straight auburn hair, tortoiseshell-frame glasses, and a thin tweed jacket. Beside her was a large package in paper, wrapped in twine.

“Mel, I’d like to introduce you to Meredith Aciendo. Meredith is from the Getty Center.”

Mel bounded over to shake her hand, which he did furiously, only stopping when he realized he was being awkward. Then he sat down.

“I’ll just let her talk,” Maggie said.

“Thanks.” Meredith unwrapped the package, carefully untying the twine. Mel recognized it. Intimately.

“Look familiar?” She said.

“Of course. How did you? I mean, where?”

Meredith slid it forward. “The Getty Center isn’t in the habit of throwing away art, even when it’s left there by someone who runs through the galleries with it.”

“Wow,” Mel said. “Incredible.”

“So I have some questions,” Meredith said. “Namely, why we have a Roy Miller and you’re Mel Miller and they’re obviously painted by the same person?”

Mel explained his father, and what he did to Mel all his life. He also explained what “The Son” meant to him.

“That is… an incredible story.” Meredith said. “I came here to give you this, but also, I would encourage you to apply for an Artist-in-residency at the Getty Center. I can’t absolutely guarantee you’ll get it, but with a story like yours – and the fact that we’re already hanging your work – no one stands a better chance than you. It means money, it means a place to stay. All you have to do is apply and be interviewed.”

Mel was in shock. Artist-in-residency? We didn’t dream anything like this when he was fully delusional. Just one thing.

“I need to get my son,” Mel said. “He’s back with his mother, and that’s an extremely neglectful and abusive situation. I can’t just live somewhere he can’t go.”

“I looked up that too,” Maggie said. “Andy never went to New York. They tried to contact his mother, but she’s in jail. Drugs, I think they said. He’s here in L.A. county with a Resource Family.” Mel’s brow furrowed.

“Foster family, same thing,” she said. “If there’s a deal here, Mel, take it. It could be months before you get a chance to get Andy back, and you have a much better shot being on the board than off.”

“We can help you find a place while your application goes through. We’ll work with Social Services on your behalf,” Meredith said. “We take care of our own here.”

Mel thought he was going to have trouble catching his breath. Instead, adrenaline, and lots of it.

“I’m fully game, but could you all give me like three minutes? I need to do a quick run through the halls.”

RadioRadioX

RadioRadioX