Lithium, Chptr. 19 – Xperience Fiction

By Staff on December 16, 2025

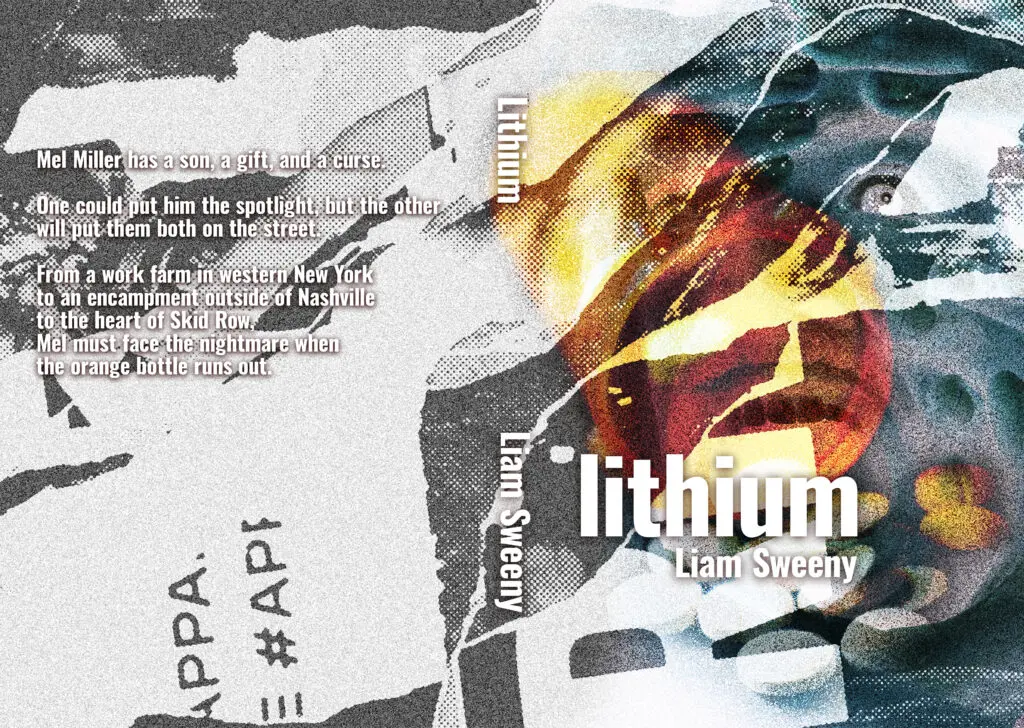

Lithium, Chptr. 19 – Xperience Fictioin – by Liam Sweeny.

If Mel was the Mel of a month ago, and he’d seen a sparse row of tents on a city street, he’d have thought that they were waiting for the latest game console to come out in a chain store down the block. He never would’ve seen it as a parallel housing complex.

It certainly wasn’t Skid Row. The tents were a little nicer and a little more orderly, and he didn’t see garbage anywhere. When they were on the Greyhound, Mel pictured them pitching a tent alone in a public park, not being one of many. He couldn’t believe how bad the homelessness problem was in L.A., or anywhere else he’d been. That disbelief helped him avoid having to count himself and his son among them.

They pitched the tent carefully, knowing that they didn’t have scrap to support it if they tore anything. Once they finished throwing the sleeping bags in, the four-person tent felt stuffed with only three people. Mel wished they had lawn chairs, but lawn chairs didn’t travel well.

Hope wandered around the block on reconnaissance, looking for anything useful. Mel realized he hadn’t had much alone time with his son since they left the farm. He felt guilty because he knew that it wasn’t entirely unavoidable.

“You okay, kiddo?”

Andy shrugged and set his eyes to his lap. “I guess so,” he said.

“You guess so. I know it’s tough right now, but we’ll-,”

“Get through it? You say that, and every time it just gets worse.”

“I know, I know, I’m really trying. You have to believe me.”

“I had a hot dog today, and a cup of yoghurt for breakfast. How are we even eating tomorrow?”

“I don’t know, but Hope knows places to go around here. She’ll help us out.”

“So Hope to the rescue, yet again?”

Mel took a breath. “Okay, what’s wrong with Hope?”

“Nothing,” Andy said. “There’s nothing wrong with Hope. It’s you.” Andy picked up his box of cards, one of the things Mel was able to fish from the minivan.

“That’s fair,” Mel said. “I’ve let you down a lot lately.”

“It’s not fair. You don’t even know my problem with you right now, Dad.”

“Well, tell me,” Mel said. “I’m listening.”

“For starters, this is the first time you said ‘I’m listening’ since we ended up in Nashville. It only started with Hope. Once she was around, you fell all into her. The only thing you loved more than her was your painting. It was her, the painting, me.”

“That’s not true,” Mel said. “And that really isn’t fair.”

“You got off the meds and I brought you stuff to eat every day, and as soon as you were better you went off with Hope. You never spent a whole day with me after that. And that has nothing to do with Hope. That was you.”

Andy was striking a nerve. Mel felt an anxiety building up, a primal fear that he couldn’t take care of his son, and it was beginning to unravel right then and there. He pressed his temple to try to push it in, push it down, but he knew there was only one way that might work to deal with it. Honesty.

“You’re right, Andy. I passed you by when I met Hope. I have no excuse,” he said.

“That’s not it,” Andy said, his voice subdued. “You keep choosing that painting over things that can help us. You pulled it out of the minivan instead of other stuff. You brought it on the bus, instead of other stuff. Hell, you just spent how much on a storage space?”

“Yeah, I know…”

“How much?”

“Forty-nine ninety-five.”

“We could’ve used that for food, supplies,” Andy said. “How much do you have left, and be honest with me?”

“I have about fifty left,” Mel said. “Maybe a little less.”

“So you spent half of our money on a painting that you can repaint some other time, because you have a photographic memory and you can do that kind of thing. You’re not being responsible at all, and you leaning on Hope scares me, Dad.”

Mel rubbed the back of his head, combing through rough hair that would likely never get cut in a barbershop.

“There’s a story to the painting,” Mel said.

“You’ve told me,” Mel said. “I had colic, and you stayed up at night, painting it.”

“You didn’t have colic,” Mel said. “You had…issues… when you were born. In fact, you have a condition named after you in some medical journal somewhere. They treated you in the NICU for a month before we could take you home.

“I had to watch you every night, because if you started showing certain symptoms, it was trouble. And bipolar affects sleep, even when you’re on meds. So I was terrified that I’d fall asleep and wake up, and you’d be…” Mel paused. “You’d be in trouble.”

“So I painted, and painted, and painted. There are so many paintings on that actual canvas. But I used it to prove I could be good at something, and if I could paint the perfect thing, then I could be a good dad. I know that might not make sense, but it did to me at the time.”

Andy was quiet for a moment too long for Mel’s comfort.

“I’m scared, Dad.”

“I know, Andy,” he said. “I am too. Do you want me to find a way to send you back home? Do you want to take your chances with your mom? There’s food and walls there anyway.”

Andy waited a minute before speaking. “No,” he said. “Not yet.”

“Just give me a chance,” Mel said. “I have that painting for a reason. I don’t love it more than you, believe me. I love it because I love you. I want to use it to get us somewhere where we won’t need tents and sleeping bags. I haven’t given up hope, and as far as Hope, the person, give her a chance. We do need her in our lives. Even you.”

***

Mel’s sleep was scattered, and when he did get to sleep, he dreamt of a usual haunt for his dreaming landscape. He was in a house, on the outside simple and plain, but once inside there were rooms where he wouldn’t think there’d be rooms, whole levels and garages that couldn’t possibly fit in such a small house. He never could remember what he would do in the house, though there was furniture down to the doilies. He could’ve drawn the blueprints were he able to remember it when he woke up.

But in this dream, he was in a tent. He was naked, and he knew that Andy and Hope were missing, but he didn’t know how to get out of the tent. And to top it off, his father was tapping on one of the tent poles. And before he knew it, Andy and Hope were outside of the tent, tapping on the tent poles, calling him out. Then somehow, they were shaking him.

“Get up, c’mon,” a voice said. Not his father. Not Andy, not Hope. But his hand was on Mel’s arm, and he was leaning into the tent, trying in earnest to pull Mel out. And he was in uniform.

Mel tried to wipe reality back into his mind so that he could understand what was going on. As soon as he tried to sit upright in the tent, the cop started pulling him out.

“Hold on, I’ll get out!” Mel shouted. “Just give me a second.”

The officer didn’t have, nor care to have, a second to spare. Odd fact was that it would’ve taken less time to get Mel out had the cop just let him come out on his own. But maybe cruelty was the point.

Mel wound up on the sidewalk, his arm throbbing, and a nasty scrape on his ankle. The cop was joined by another, and they broke the tent down unceremoniously. And they weren’t alone. The whole sidewalk full of tents were slowly being dumped into a garbage truck double-parked.

Mel got up and looked for Andy and Hope, who were on the corner, Hope holding Andy and stroking his hair.

“Officer,” Mel said. “Can I at least get the sleeping bags out? We have nowhere to sleep.”

“Shouldn’t have set up here,” the cop said without looking at him. “Go camp out in Skid Row, where you belong.”

“I got a kid; I can’t risk putting him somewhere like that.”

“If you had any sense, you’d give him over to foster care,” he said. “At least he’ll have a chance.”

“If you were homeless, would you give your kid away?”

“It’s not my problem.” The cop lifted the tent.

“It wasn’t my problem three weeks ago,” Mel said. “Never imagined it would happen, but I showed mercy to homeless people because I knew fate was a bitch that kept score. I hope your family never sees this side of fate.”

The cop motioned to his partner. They flipped the tent and shook it, and the three sleeping bags fell out.

“Don’t sleep here. We’ll toss them, and we’ll toss you in jail for vagrancy. Think about foster care for your kid.”

They started walking as soon as Mel gathered up the sleeping bags. Unfortunately, the packs they came in didn’t shake out of the tent with the bags. Mel was feeling ill, and his head was distant. He wasn’t as depressed as he could’ve been. In fact, he wasn’t as depressed as he shouldn’t been. Oddly, he felt euphoric.

“He listened to me,” Mel said. “The cop. I told them a thing about fate and they listened.”

“They usually don’t.” Hope said. “You did good for a newbie.”

“This might not be so bad,” Mel said. “I can handle myself in the streets.”

“You got mercy from a cop,” Hope said. “Rare, and you won’t have that same luck from most people around here.”

“I don’t know, I just have a good feeling,” Mel said.

“That’s good. Just keep aware. Now we don’t have a tent. Getting robbed will be easier. So when we find a spot, I’ll show you a few tricks.”

They walked the perimeter of Skid Row; at least Hope told them it was the perimeter. Skid Row had a perimeter, but homelessness spilled out of it. Cops were at the edges like gangbusters trying to contain the city’s dirty secret, a cog in the effort to contain America’s dirty secret.

“There are a ton of missions in Skid Row, but they can be just as dangerous to sleep in as sleeping outside. There are soup kitchens, but they’re crowded, and you might wait in line for a couple hours just to get a meal. We’re going to have to go in there to the soup kitchens, no matter what. But I think I know a good spot to sleep. Good as any.”

They made their way to a parking garage covered in graffiti.

“We go up.” Hope started in, Mel and Andy followed behind. There were tents, but they were interspersed throughout. It wasn’t mobbed like what Mel saw when they drove through the thick of it.

“Cops clear this out too, but not as much,” Hope said. “It’s an abandoned garage. Nobody would trust their cars here.”

They went up to the top, to the open air.

“Less people mess with you when you’re up top,” she said. “They figure there’s no point going in a garage and not taking advantage of a roof over your head.”

They got up top and picked a corner, where they laid down their sleeping bags. Hope handed Mel one of the folding knives.

“Around here we do sentry,” she said. “You stay up for six hours, then wake me up for the next six. Andy sleeps full.”

“I can do sentry,” Andy said. “I want to be a part of what’s going on. And I’ll probably have trouble sleeping.”

“Nope, Hope’s right,” Mel said. “You sleep. Someone needs to be fresh.”

Turned out, both Mel and Andy could’ve been sentry all night, because neither could sleep a wink. Mel just held onto the folding knife, wondering if he had the guts, or the survival instinct, to use it.

***

Hungry people. Raw, unshowered and unshaven and desperate to count luxuries like showering and shaving again. Mothers with children with faces that rivaled those in nineteenth-century child labor photographs, coal mines. Men in wheelchairs and crutches taped up because they likely came from someone else’s trash, else they’d been ordered by a doctor who. by then, was retired. Hungry and desperate, lost even as they stood in a line for a guarantee of nourishment. Maybe a guarantee, depending upon their place in line. Make that Mel, Andy, and Hope’s place in line.

They were stretched around the front of the Fifth Street Mission and down San Julian Street, a small street, an alley, lined with tents, but not as congested as some of the worst places Mel had seen. It was weird to him that the more obscure places wouldn’t have more tents.

But the more he thought about it, the more his mood lifted. It was pride. People wanted to set up a tent on a busier street because they wanted to be seen by the cars that came through. They wanted to matter; they did matter, in the way the average workaday, clockwork, stock-standard person could ever matter. They were the proof that the commercials and the propaganda couldn’t counter, and the kind of life that held fast to the maxims of glory and determination and struggle couldn’t fathom any of them not rinsing a body of the filth.

Mel looked around and he saw people who worked harder than everyone, with not a second’s peace, and at the end of the day, however hard, they were back where they started. The American dream was out there, but it took a good night’s sleep to have it.

“A penny for your thoughts?” Hope said.

“I was always ashamed,” Mel said. “When I saw people on the street. And I didn’t know why. And I felt pity, but that’s what you’re taught to feel.”

“Different on this side of the trash can, isn’t it?”

“I feel… almost pride in the people here. Like an admiration.”

“Any one of them will steal your shoes,” Hope said. “Or worse.”

“But not all of them, and they’d only do it because they’re desperate.”

“You’re desperate right now. And shoeless if you let your guard down to the wrong person.”

The line moved slowly. Mel wondered if they’d have any soup for them by the time they got in. He figured he’d strike up a conversation with the man behind him in line. He had a shirt with a leprechaun and a pot of gold on it. He was probably easygoing.

“How long you been on the street?” Mel asked.

“Stop that,” Hope said. The man spit on the ground.

“I’m Mel. Mel Miller.” He held out his hand, and it hung.

“Clyde.”

“So how long you been out here, Clyde?” Mel said. “I’m new myself. Only been homeless for maybe a month. I’m a painter.”

“Is that right?” Clyde said.

“Yeah. I can paint anything I can see. I have a photographic memory.”

“Oh yeah?”

“He doesn’t care, Mel,” Hope said. “C’mon, we need to move, the line is going.”

“Best get on that line,” Clyde said. Mel waved, and he noticed he was still tapping his fingertips. Weird; he hadn’t done it in a while.

They moved up in line. Hope was looking everywhere but at Mel. Andy was looking only at Mel.

“You’re acting weird, dad,”

“How’s that?”

“You’re cheery and you’ve been talking more than usual.”

“There’s nothing wrong with being cheery,” Mel said. “And I have a lot to say. If you talk right, and say the right things, you can really get somewhere. Politicians start wars with words, and writers, hell, they’re full of words. Why am I weird for using words?”

“You’re not a writer or a politician,” Andy said. “And you’ve gone up to three strangers today, just talking to them. One of them in the garage looked like he wanted to punch you in the face.”

Andy let it go, and the line kept moving. Mel tried to keep a lid on it, but every so often he’d tell Andy or Hope something. They were ignoring him and quiet. So he’d have to be the sociable one.

There was a straight shot to the dining room from the entrance. They walked into the diluted smell of food and the undiluted smell of antiseptic cleanser. Mel knew the smell, as they used something very similar at ArTechnic. There was a long counter with a sneezeguard that was tall enough to shield the servers’ faces. As they moved through, there was good cheer coming from some of the diners who apparently knew the servers. It was warming Mel’s heart.

They got soup and bologna sandwiches and pints of whole milk, on plastic trays that weren’t alike. Even the soup kitchens there were thrift. They took a seat near the back, where an older black man with a Vietnam hat on was sipping soup with his head near the bowl. Mel smiled and waved.

“That your boy?”

“Yeah, he is,” Mel said. “I’m Mel.”

“Bet you are,” the man said. “Damn shame you here with a little boy. He got a mother?”

“She’s pretty bad.” Mel said. “He does, though.”

“You got someplace to go?”

“Sure, we’re at-,” A jab to his ribs made him take a breath. He looked for the source, and it was Hope. Her eyes were lava. He figured he should shut up.

“It’s no matter,” the man said. “I stay at Bethlehem Mission on South Los Angeles, Between East Third and East Fourth. It’s okay, so it’s tough to get in, but I’m a veteran; they let me in. They probably let you in for a couple nights, you being a family and all.”

“Thank you, sir,” Hope said. “We’ll look into it.”

Hope handed Mel his spoon. Signal given. Mel managed to eat his whole meal in silence, shelving the urge to talk. He noticed that he wasn’t hungry, though by all accounts, he should’ve been famished. They finished and got up. As they passed by the edge of the serving counter, Mel caught the last server’s ear.

“I’ve found that bone broth gives the soup a fuller flavor, and if you sauté the mirepoix ahead, instead of just dumping them in the broth, you’ll get a really satisfying chew, and the broth will be-,”

“Thank you, it was very good,” Hope said as she grabbed his arms and pulled him toward the door.

RadioRadioX

RadioRadioX